So, assuming that your first sentence has fully grabbed the attention of the reader, your first paragraph (Introduction) must accomplish some basic objectives.

Tag Archives: Susie Helme

Openings – First Sentences

If you want someone to read your book, you must ‘hook’ them by your first paragraph—ideally, by your first sentence. Potential publishers or agents may ask you for your first 3 chapters, but in practice they often read only the first paragraph before rejecting you.

Write Natural Dialogue

The biggest mistake I see is sentences that begin with ‘You know…’ It is not natural for people to say things the other person already knows. Ask yourself—which bits of the speaker’s conversation are new news to the other person, the interlocutor?

Write What You Know?

Mark Twain’s advice to writers was to ‘write what you know’, but I’m terrible at taking advice. I’ve written about first century Jews, and I am not a Jew, and 14th century Muslim lesbians, and I am neither a Muslim nor a lesbian. I’ve always been driven by the desire to learn about new things. I want to find out absolutely everything about what I don’t know, and once I do, I want to impart that experience to others.

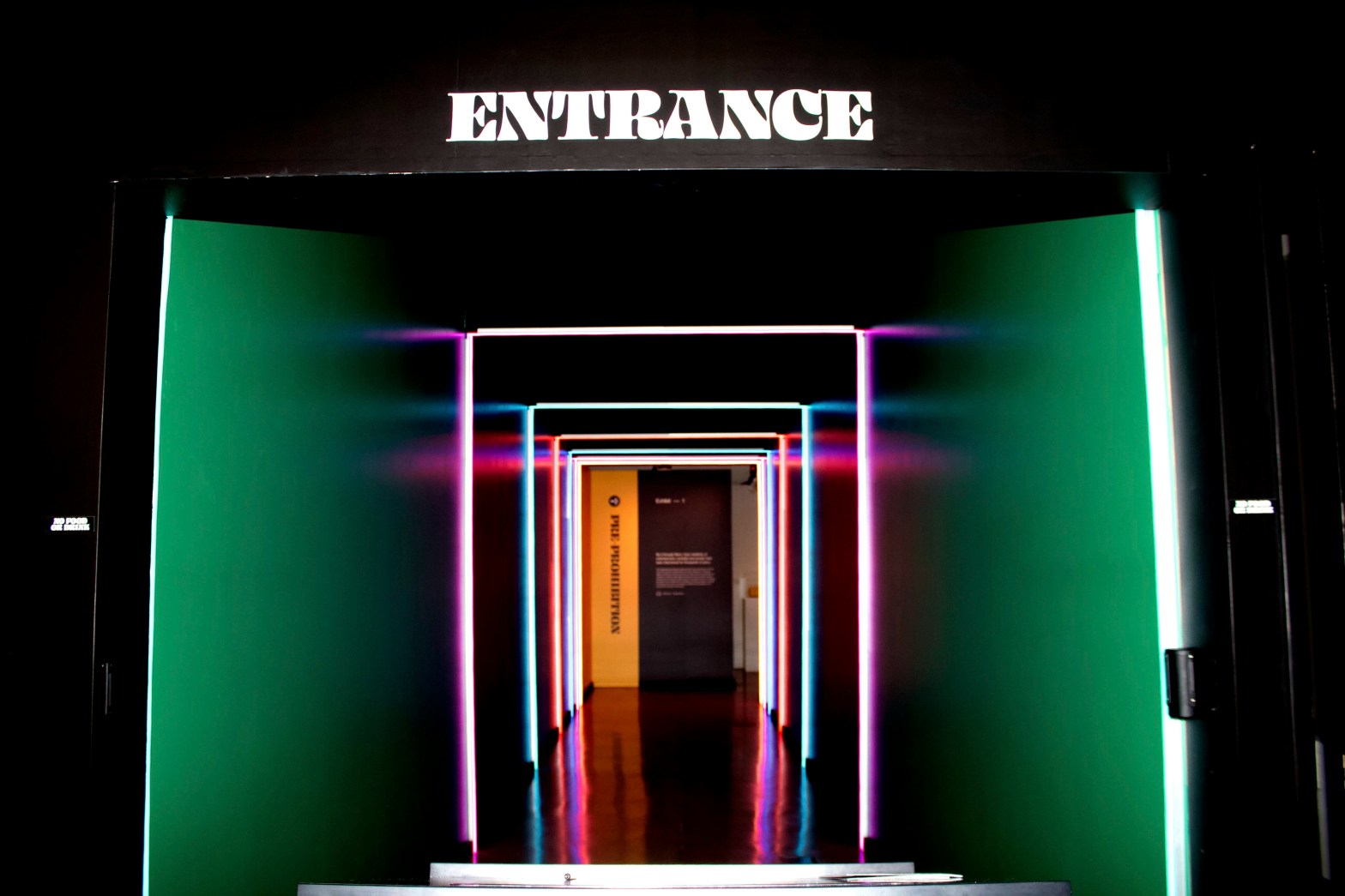

Writing Intros

Your first 100 words are the most important words in your novel. Often these are the only bits an agent/publisher will look at, before tossing you onto the Reject pile, so it’s worth making an extra effort. If you haven’t grabbed the reader’s attention by then, they will move on to pick up the next book at the bookstore or scroll to the next selection on Amazon.

Using props

I listened to an interview with Michael Caine, recounting an incident he learned something from as a young actor. He was in a scene where a brouhaha between a man and wife had resulted in some violence, and a chair became lodged in the doorway. He said to the director, ‘I can’t go in the door, as there’s a chair stuck in the way’, but the director advised him to ‘use the difficulty’.

Against ‘and’

It’s usually not good writing to use the construction ‘x and y’. It’s indecisive. You are trying to convey something to the reader, so make up your mind what is it you’re trying to convey. x or y? This is one place where Less is More.

Against clichés and purple prose

Watch out for adverbs or adjectives that seem inextricably glued to your noun or verb like a Homeric epithet. In the Odyssey, dawn must be ‘rosy-fingered’; Zeus must be ‘far-seeing’; the sea must be ‘wine-dark’. But you are not Homer. Not all halts are ‘screeching’. Not all hot days are ‘scorching’.

More thoughts on writing historical fiction

Whether you’re writing about real historical characters or invented historical characters, your goal is still going to be the same as it is for all fiction writing. You need to address the elements: character, dialogue, setting, theme, plot, conflict, and world building.

Historical fiction: Die, Die, Die

Continuing our historical fiction theme, in this week’s instalment, an ancient Briton fights the Roman invaders.